From the early 1900s, Number 47 Downshire Hill was a place where artists, activists and political refugees met to discuss and record the unfolding events of the new century.

The house at 47 Downshire Hill is an imposing building occupying the prow of the mid-section of the street. It was built, along with the other late Georgian houses of Downshire Hill, in the early 1800s. From its wide roof top windows and deep terrace, the house has a commanding view over Downshire Hill, St John’s Chapel and far off into the distance over Hampstead Heath. A cockerel weather vane, perched high on the rear roof, keeps watch over the daily comings and goings down Keats Grove.

Since its earliest days, number 47 has been a magnet for artists, political activists and writers, sometimes the focus of Hampstead’s emerging modernist art movement, at other times, political refuge for anti-Nazi, European asylum seekers.

By the late 19th Century, Hampstead had cemented its reputation as an out-of-town centre of rejuvenation from the stench and overcrowding of central London. Up on the hill, with clean air and fresh water springs, the village attracted weekend crowds, and day trippers eager to catch a glimpse of this prosperous village. In 1889, Charles Booth described Hampstead as a place where ‘building is entirely for the rich.’ and that its inhabitants were ‘middle and upper class business and professional men, merchants, authors, journalists, musicians and others.’

For more than 100 years, its wild landscape, clean air and relative quiet had given both inspiration and solitude to artists and writers. By the early 1900s many creative minds had followed the likes of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Elizabeth Siddal, John Constable, Leigh Hunt and John Keats making it known as a notable area of artistic, literary and scientific output.

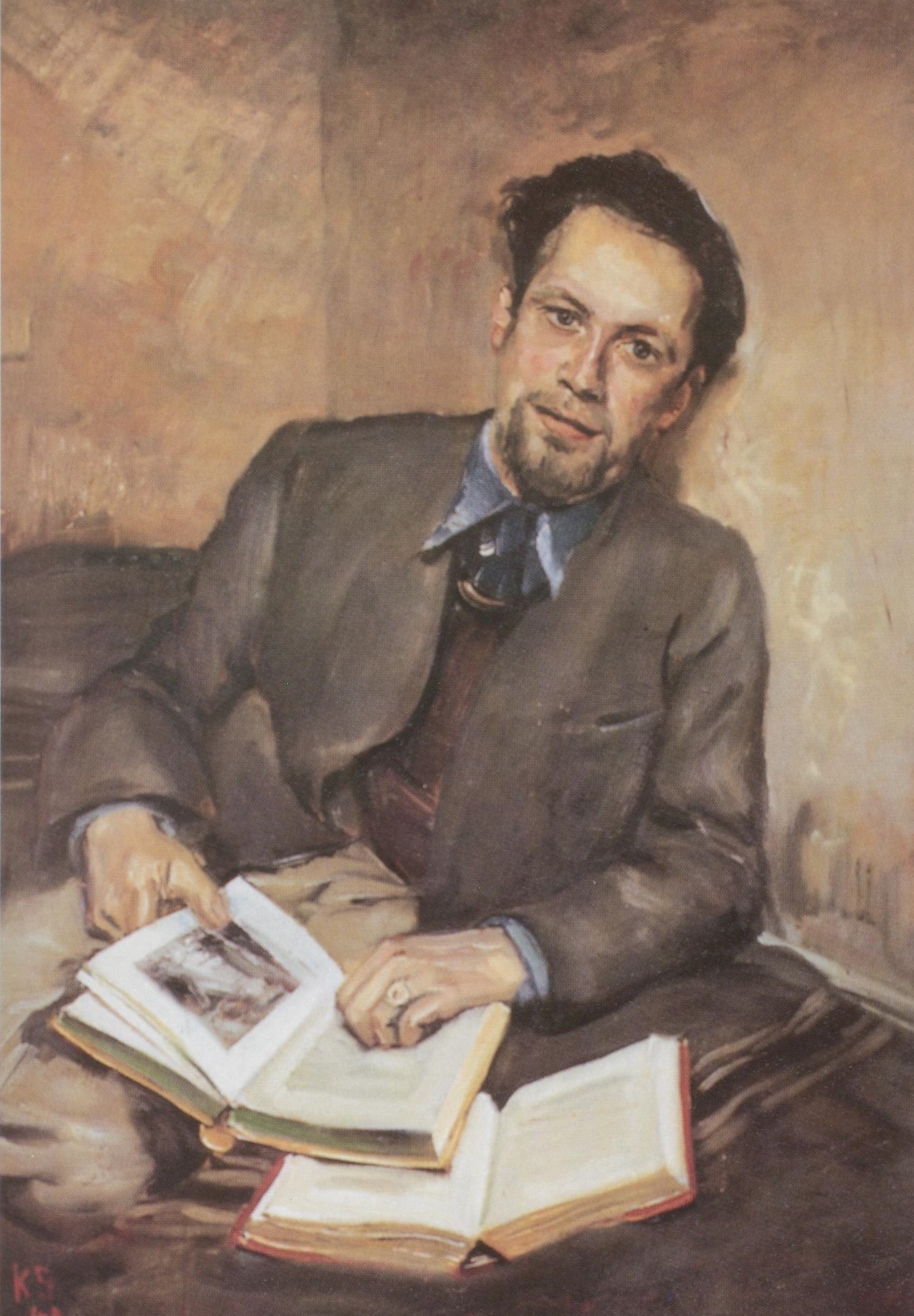

John Heartfield

A blue plaque at 47 Downshire Hill commemorates the occupation of John Heartfield (1891-1968), inventor and master of political photomontage. Heartfield was a German born, left-wing political commentator, who turned to film and photomontage as a way of exposing fascist and nazi propaganda of early 20th century Germany.

Heartfield was born, Helmut Herzfeld in 1891. In 1899 at the age of 8, he was abandoned by his parents in a Swiss mountain hut. Along with his siblings, Wieland, Lotte and Hertha he was brought up by his uncle in a remote village in Austria.

His first act of public dissent was to anglicise his name from Helmut Herzfield to John Heartfield in protest against anti-British sentiment during the first world war.

Heartfield lived in Berlin until April 1933 when the Nazi Party took power. On Good Friday, the SS broke into his apartment, but he escaped by jumping from his balcony and hiding in a bin. He was number five on the Gestapo’s most-wanted list at this time.

He fled Germany by walking over the Sudeten Mountains into Czechoslovakia. In 1938 with the threat of the imminent occupation of Czechoslovakia, he fled to England, initially living with Yvonne Kapp (1903 – 99), a Czech journalist, novelist and political activist.

Penniless and barely able to speak English, he was unable to find work and forbidden to do so by the British Government. Even so, in 1939 he managed to organise a solo exhibition at the Arcade Gallery in Old Bond Street entitled ‘One Man’s War against Hitler’ organised by the Free German League of Culture founded by the Viennese émigré Paul Wengraf.

Finding it difficult to settle in a foreign country, he found accommodation through fellow émigré artist Fred Uhlman and his wife Diana Croft. Fred was one of the founding members of the Free German League of Culture and it was through this connection that John found himself living at the home of the Uhlmans in Downshire Hill.

John was keen to follow his brother Wieland who had been granted permission to emigrate to the USA in 1939. However, he was denied permission and had to stay in England for the foreseeable future. In 1940, at the outbreak of the Second World War, he was interned as an enemy alien, being held in 3 different camps over 6 months. It was as a result of his poor health that he was allowed to leave the camp, returning to Hampstead.

His peak moment of artistic fame seemed to be fading, the Home Office refusing to allow him to work as a ‘freelance cartoonist’. During this time, he was an active participant in the Free German League of Culture, as a stage designer and exhibition designer, most notably that of the exhibition ‘Allies Inside Germany’, aiming to convince the British public of potential allies in that country.

Heartfield turned 50 in 1941 and at the time English art historian Herbert Read wrote of him: “John Heartfield is one of those rare artists who have extended the range of our aesthetic sensibility by inventing a new technique. He has seen the creative possibilities of montage – of the photograph as a plastic material which can be manipulated and made to produce effects independent of its mechanical origin.”

Still denied permission to work, he became more the collector than creative. He amassed a huge collection of articles, photographs and war records which is now part of the John Heartfield archive in Berlin. It was only after 1943 that he was allowed to return to his chosen discipline, with letters of support from amongst others, Leonard and Virginia Woolf.

Through the 1940s, he then made a steady living working at the Lindsay Drummond Publishing House, visualising the political culture of the publisher through his unique drawings, text and photomontage.

Heartfield married Gertrud ‘Tutti’ Fietz, after which he moved from Downshire Hill to 1 Jackson’s Lane in nearby Highgate. At his departure from the Uhlmans’ house, Heartfield was given a pair of rabbits, which quickly multiplied in number, forcing Heartfield to spend hours every day gathering food for them on Hampstead Heath. (From the book Burning Bright, Essays in Honour of David Bindman, chapter title “John Heartfield: A Political Artist’s Exile in London.” Chapter author, Anna Schultz.)

Heartfield was offered a professorship in Berlin in 1950, a post he reluctantly accepted finding it difficult to reconcile the idea of moving back to the country he had so recently fled. He died in on the 26th of April 1968 and is buried in Berlin.

For more information, see this catalogue from the 1992 exhibition at the Met, New York.

The Uhlmans

Heartfield was given lodgings at 47 Downshire Hill by the owners, Fred and Diana Uhlman. Diana was a prominent figure in the art world, and by all accounts a rebel of her time. A political activist, she was born to conservative parents, Nancy Beatrice, born Borwick, and the politician Henry Page Croft, first Baron Croft. Henry was a co-founder of the National Party and proponent of an extreme version of Chamberlain’s Tariff Reforms; which carried with it a ‘shriller note of xenophobia that seemed in tune with the spirit of the times1‘.

For Diana, life often seemed a series of events, vigorously opposed by her conservative parents. She married Fred Uhlman, a German refugee whom she met in Tossa de Mar, Spain in 1936. Uhlman was the son of a prosperous middle-class Jewish family, a graduate in law with a Doctorate in Canon and Civil law. As a refugee, he lived in Paris for a short time, supporting himself through the sale of his drawings and paintings. In early 1936 he arrived in England and married Diana on the 4th of November of that year.

After purchasing 47 Downshire Hill in 1938, she opened it up as a meeting place for refugees and exiles who had been forced to flee their homeland. Fred and Diana were founder members of the Artists’ Refugee Committee and Free German League of Culture, organisations which ensured that artists such as Oskar Kokoschka and John Heartfield, both Czech residents in 1938, were able to come to England and settle here.

In 1940, Fred Uhlman, along with many German refugees was interned in Hutchinson Camp on the Isle of Man. His daughter Caroline was born whilst he was there. He was released after 6 months. Fred wrote many books, his most famous, ‘Reunion‘ a semi-autobiographical novella describing the fate of two young German boys, one Jewish, one Christian at the outset of WWII.

Their daughter, Caroline Compton continued to live on Downshire Hill at numbers 47, 48 and 41.

The Carline Family

Prior to Heartfield’s time at 47 Downshire Hill, the Carline family had been long time residents of the house. George and Annie Carline first came to Downshire Hill in 1916, purchasing the house from author and doctor, Edward Wright.

George, an artist, had met Annie during a stay in Essex where he had been commissioned to paint a portrait. At the time, Annie was living with relatives who had adopted her at birth. George and Annie married in 1885 and initially lived in London, then at 3, Park Crescent, Oxford, Switzerland, Derbyshire, returning to London to live in Hampstead.

George and Annie had five children, three of them, Richard, Sydney and Hilda, all become artists. Annie took up painting in her mid-60s and her talent was considered comparable to her husband’s. Richard studied art in 1913-14 at the Académie de Peinture in Paris under impressionist, Percyval Tudor-Hart. Hart also taught Hilda in London after he had established his school in Hampstead. All three went on to study art at The Slade School, Richard in 1913, Sydney between 1907 and 1910, Hilda studying part time after 1918 under Henry Tonks.

Every year, the Carline’s travelled to Assisi in Italy on painting holidays and it was on one such trip in 1920 that George fell ill and died.

After George’s death, the Carlines focused their attention on life in London. In 1920, Richard had been elected to the London Group and between 1921 and 1924 he studied part time at the Slade School of Art.

Richard’s 1925 painting Gathering on the Terrace at 47 Downshire Hill, Hampstead depicted several of his art friends and members of his family. Regular visitors to the house included artists Henry Lamb, Mark Gertler and John Nash. Stanley Spencer and his brother Gilbert lived at 47 for a short time, the former the subject of a study by Richard Carlinefor the now famous terrace painting.

Many of Richard and Hilda’s artworks show family and friends and views from 47 Downshire Hill. ArtUK has a great article on Hilda Carline which features many of the paintings undertaken in and around 47 Downshire Hill. Burgh House in Hampstead hosted an exhibition in 2023 entitled “Those Remarkable Carlines” where many of these artworks were on display.

Both Richard and Sydney became war artists. In 1919 both brothers were commissioned by The Imperial War Museum as official war artists for the Royal Air Force. Their work led them to the Middle East where they undertook many flying missions to document various sites and battle areas.

For a time, Hilda, Richard and Sydney occupied 14a Downshire Hill, the former school building opposite St John’s Chapel, using this as their painting studio. It was in this space that Richard created ‘Studio Interior’ and his now famous, ‘Portrait of Hilda Carline’ both in 1918. After WWII, the space was occupied by Mary Kessell, also an official war artist, who furnished it with textiles and paintings; Sir Kenneth Clark, a nearby resident and her sometime lover, became a regular visitor. Clark set up the War Artists’ Advisory Committee in 1939, commissioning amongst others, Mary Kessel, Gilbert and Stanley Spencer, Patricia Preece (Stanley’s second wife after Hilda Carline), Duncan Grant, John and Paul Nash, Eric Ravillious and other important turn-of-the-century artists.

Sydney died on the 14th February, 1929 after a bought of pneumonia which he contracted following a visit to the artist John Nash. After his death, Richard donated many of Sydney’s artworks to the Imperial War Museum.

The family lived at 47 Downshire Hill for 22 years, from 1916 up until 1938.

Footnotes

- Rubinstein, W. D. (1974). Henry Page Croft and the National Party 1917-22. Journal of Contemporary History, 9(1), 129–148. http://www.jstor.org/stable/260272. ↩︎